American Whitewater Article

Returning Rapids to the ColoOriginally Published in American Whitewater Mar/Apr 2022, reprinted as an Affiliate Clubrado River

By Jack Stauss, Glen Canyon Institute

Originally Published in American Whitewater Mar/Apr 2022, reprinted as an Affiliate Club

On a Sunny October morning, I hauled gear from a United States Geological Survey truck down to the bank of a wide, churning Colorado River. Stuff you’d expect for 28 people—Paco pads, stuffed and rolled dry bags, food and beer for six days in giant coolers. But, with the mission of the Returning Rapids Project, there was much more being loaded onto rafts. We had Pelican cases holding ultra accurate GPS survey units, buckets of sample tubes, notebooks, tripods, even a hand-held x-ray gun for identifying grain composition. A late season Meander Cataract trip is always an adventure, toeing the line between sublime and extreme. For us it would be more than rock dodging and desert relaxation. Especially for trip leader Mike DeHoff.

This trip was a full-on production, one that Mike would work hard to keep on track to accomplish the goal of surveying a restoring river. To him, it’s an exhausting labor of love. Mike and his partners Meg, Pete, and Jamie have been down this section hundreds of times and care passionately about the place. In 2013, they started keeping track of a really interesting phenomenon that they realized was worth the effort of tracking.

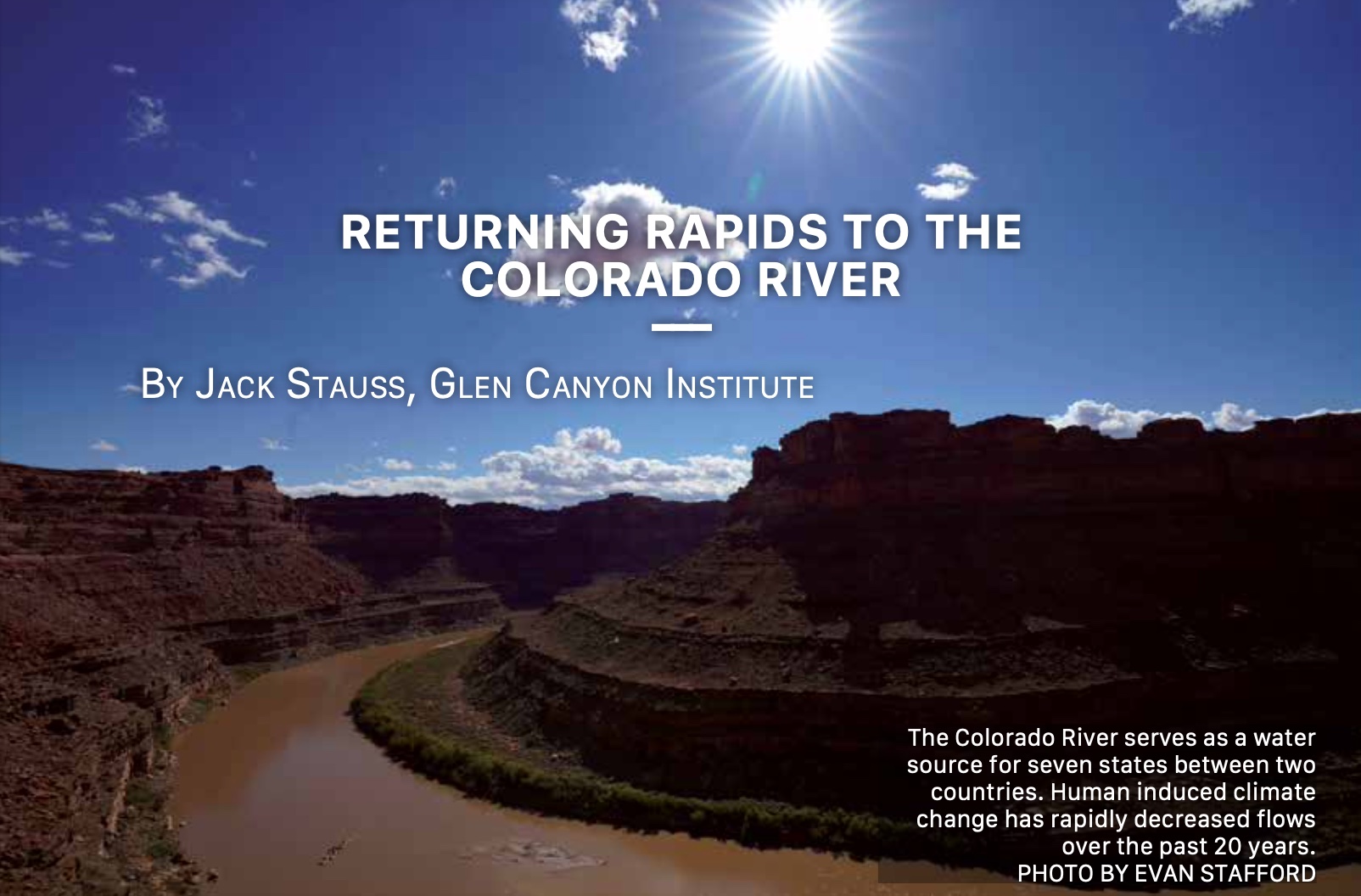

When Mike first ran Cataract in the 90s, Lake Powell was full. He tells the story of spilling out after Big Drop 3 onto a cold, emerald reservoir. Jet skiers and houseboats motored around in the pool below the rapids, a surreal civilization check after having spent several days in the remote Canyonlands National Park.

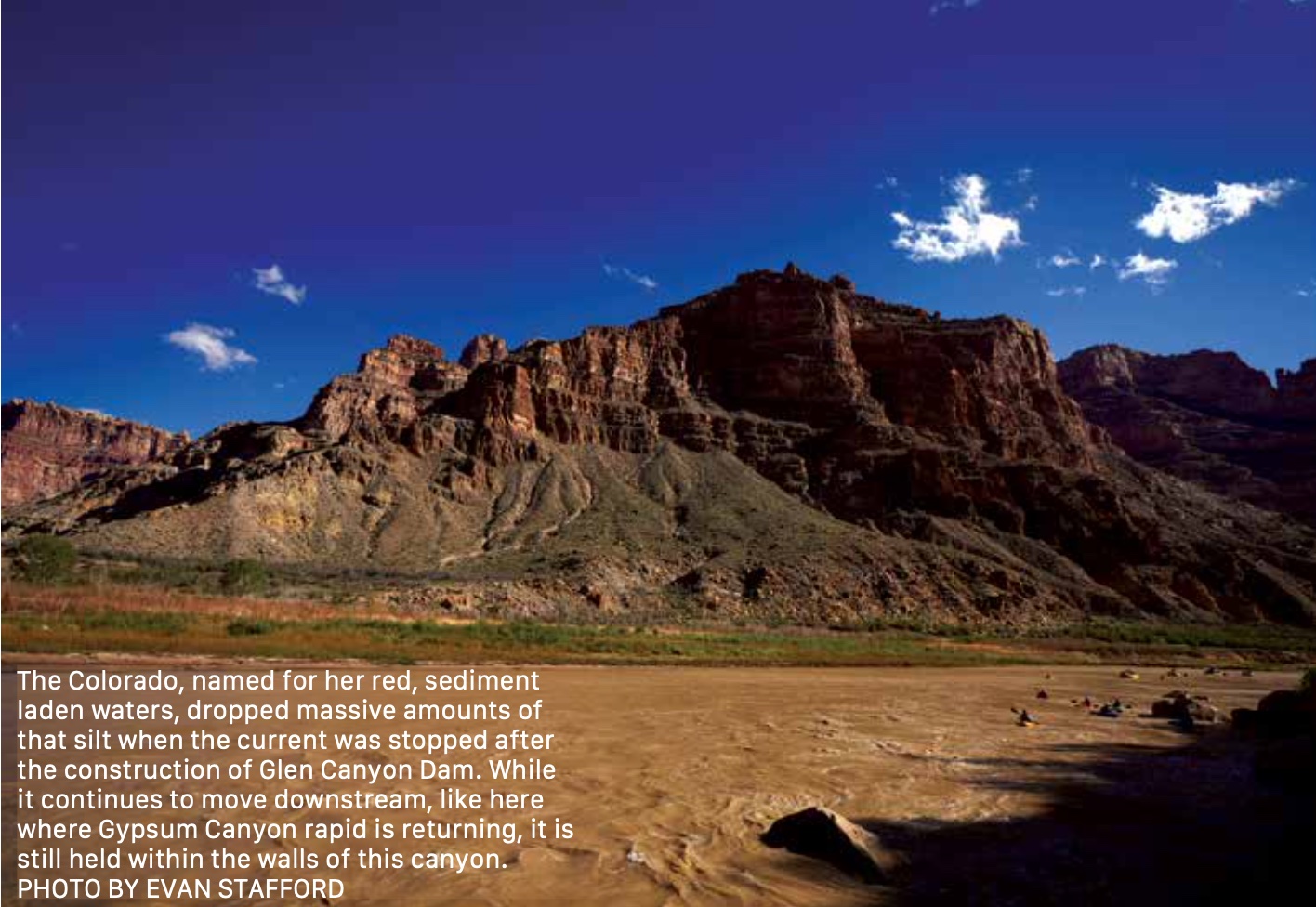

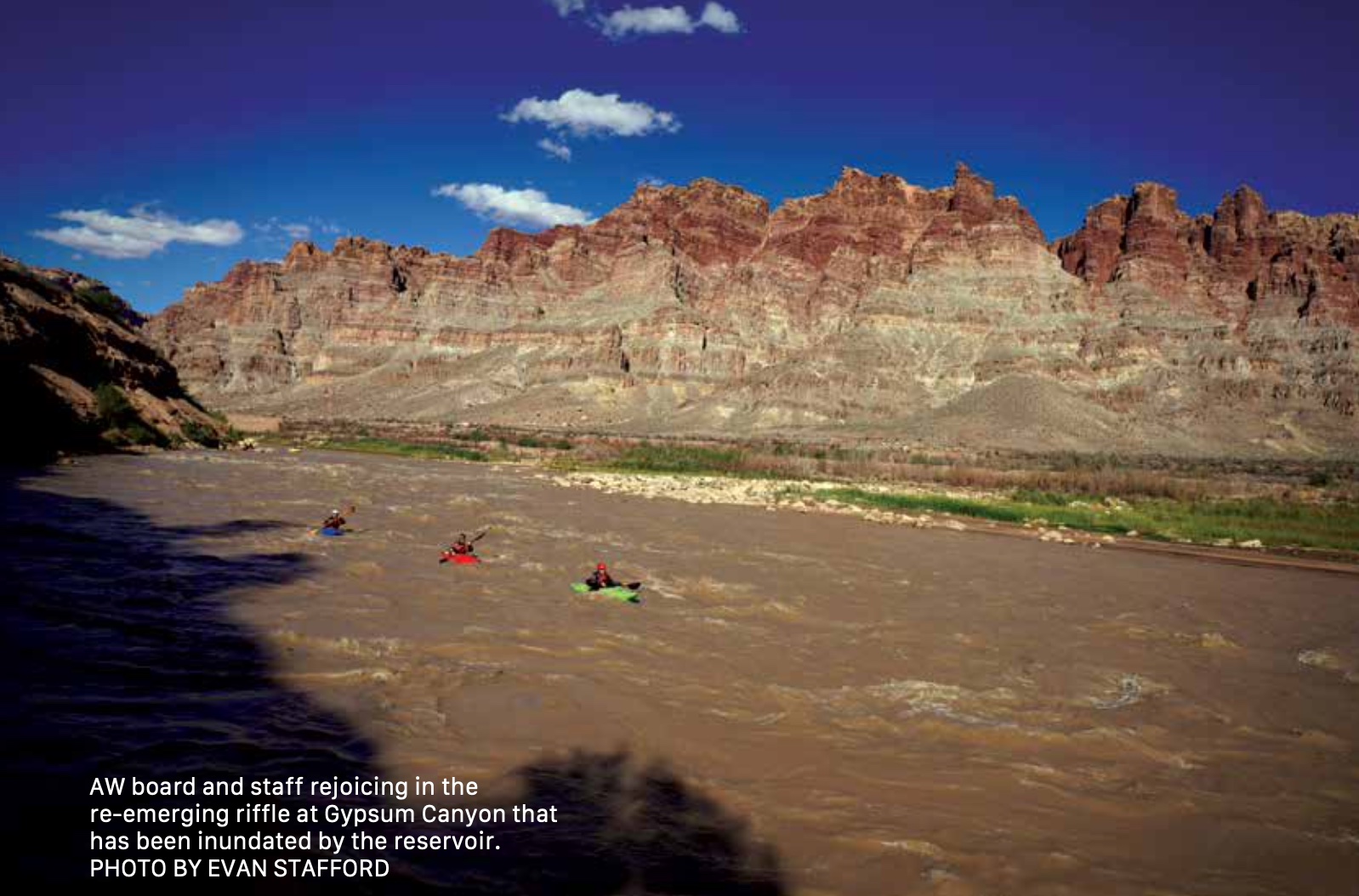

Those days are gone. The Millennial Drought, 20 years of reduced runoff brought on by an over allocation of water combined with climate change, caused aridification and the reservoir has slowly receded. These days it would be impossible to visualize the Lake Powell Mike first experienced. Mile upon mile of river now flows beyond Big Drop 3. Recently drowned rapids and new amazing hikes up side canyons now await the desert explorer.

In 2013, as they began to notice the placid waters recede, Mike and Pete decided to closely watch this transformation. They asked a simple question, “When will we start to see rapids and a living river return from the reservoir?” They identified benchmark rocks or features to understand changing water and sediment levels compared to historical photographs of the river. These started to give them a roadmap of changes taking place. Soon enough, they started to see whitewater. Starting as small wave trains and riffles and eventually becoming Class II and III rapids, the river through Cataract Canyon was restoring itself in ways no one could have imagined during full pool Lake Powell.

Fast forward to 2021. Their project has garnered interest and support from myriad researchers and advocates. The Returning Rapids Project continues to ask and uncover more important questions as it becomes clearer that a full Lake Powell is out of reach: Who manages the returning river and access to it? How should we protect the restored river and side canyons? Is the deposited lake sediment potentially dangerous? While we will likely not answer these big questions on this trip, we do hope to collect information that can paint a picture of what is happening and how quickly things are changing.

Fast forward to 2021. Their project has garnered interest and support from myriad researchers and advocates. The Returning Rapids Project continues to ask and uncover more important questions as it becomes clearer that a full Lake Powell is out of reach: Who manages the returning river and access to it? How should we protect the restored river and side canyons? Is the deposited lake sediment potentially dangerous? While we will likely not answer these big questions on this trip, we do hope to collect information that can paint a picture of what is happening and how quickly things are changing.

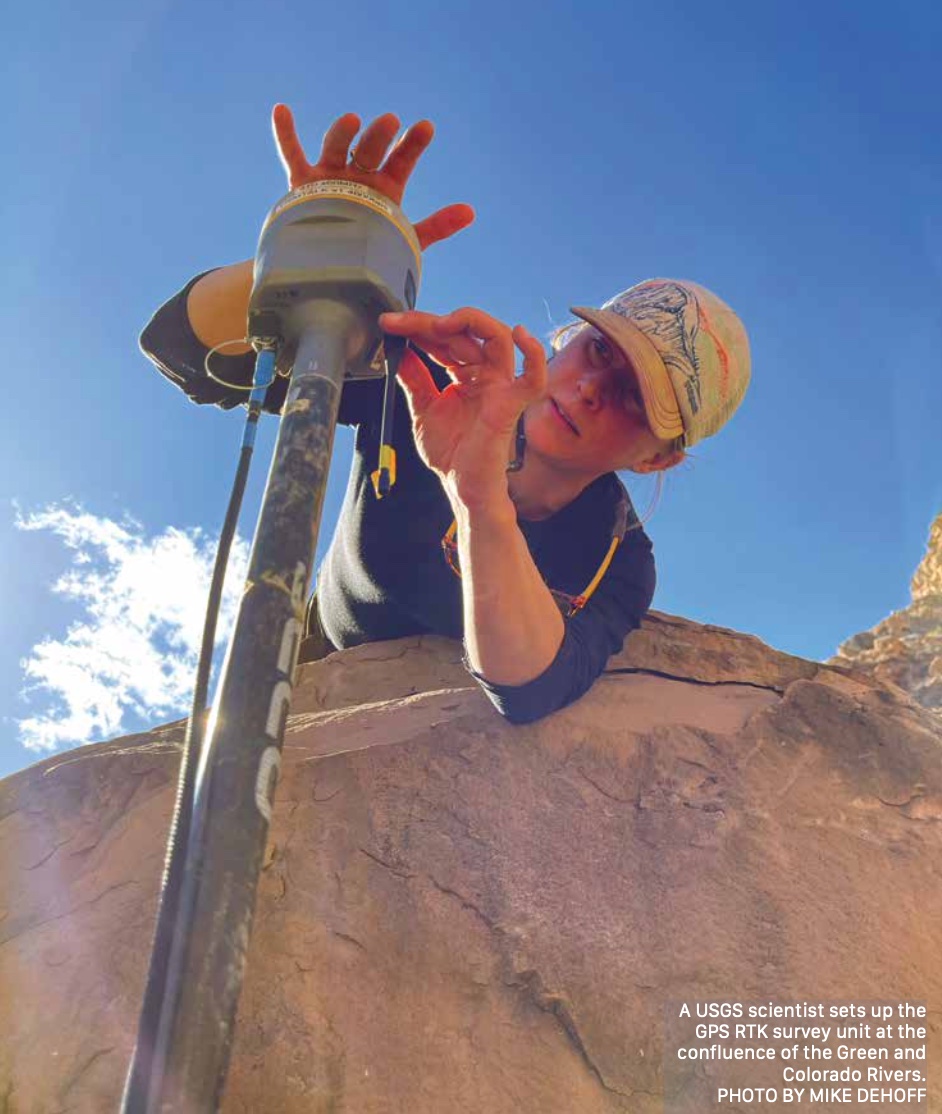

While our final boats were being rigged, Paul Grams from Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center (GCMRC) and Scott Hynek from U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) explained how to map the bottom of the river corridor. This has not been done since 1921. A central goal of this science trip was to get a new and accurate understanding of what the channel looks like now, so we can compare a pre- and post-reservoir river.

After our crash course in GPS imagining, we boarded our boats midmorning and began our journey into one of the wildest places in the country. I took my place among the “mothership,” a flotilla of boats making miles downstream. Along with other professional environmental advocates, photographers, and journalists, I was there to help lug gear and eventually to share the story of this work. Separately, other boats launched. The GCMRC vessel took river bottom readings with the survey boat. A USGS boat with a small outboard would become known as the vessel of the “sand people,” collecting sediment samples along the way. A “hasty boat” was sent to set up the control survey units at established locations further down. Finally, the fish biologists launched and set out to find the threatened humpback chub.

Conversations about the river’s past and future filled the morning. Jack Schmidt, the legendary Utah State University professor and Center for Colorado River Studies head, told us stories from his time studying the rivers of the Colorado Basin. He spoke of moving parts in Basin management and a recent trip with policy bigwigs. There were big questions on the boat and some big decisions on the horizon. We floated and hiked and waved to the sand people as we saw them running around on a beach collecting samples. While it comprised many different activities, the fall 2021 trip ultimately was a trip about sediment, or as Mike DeHoff calls it, “The Mud.”

Conversations about the river’s past and future filled the morning. Jack Schmidt, the legendary Utah State University professor and Center for Colorado River Studies head, told us stories from his time studying the rivers of the Colorado Basin. He spoke of moving parts in Basin management and a recent trip with policy bigwigs. There were big questions on the boat and some big decisions on the horizon. We floated and hiked and waved to the sand people as we saw them running around on a beach collecting samples. While it comprised many different activities, the fall 2021 trip ultimately was a trip about sediment, or as Mike DeHoff calls it, “The Mud.”

In order to really understand what the rapids below the reservoir’s high water mark are doing, we have to understand where the sediment that settled out when the lake was high ended up and how it is moving downstream. Most of the sediment work would take place below the Big Drops. We had two days of travel to the confluence, then another day of running the rapids to get there. So down we motored. I kicked back on a tube in the front of the raft barge and closed my eyes. I let the autumn desert sun warm my face.

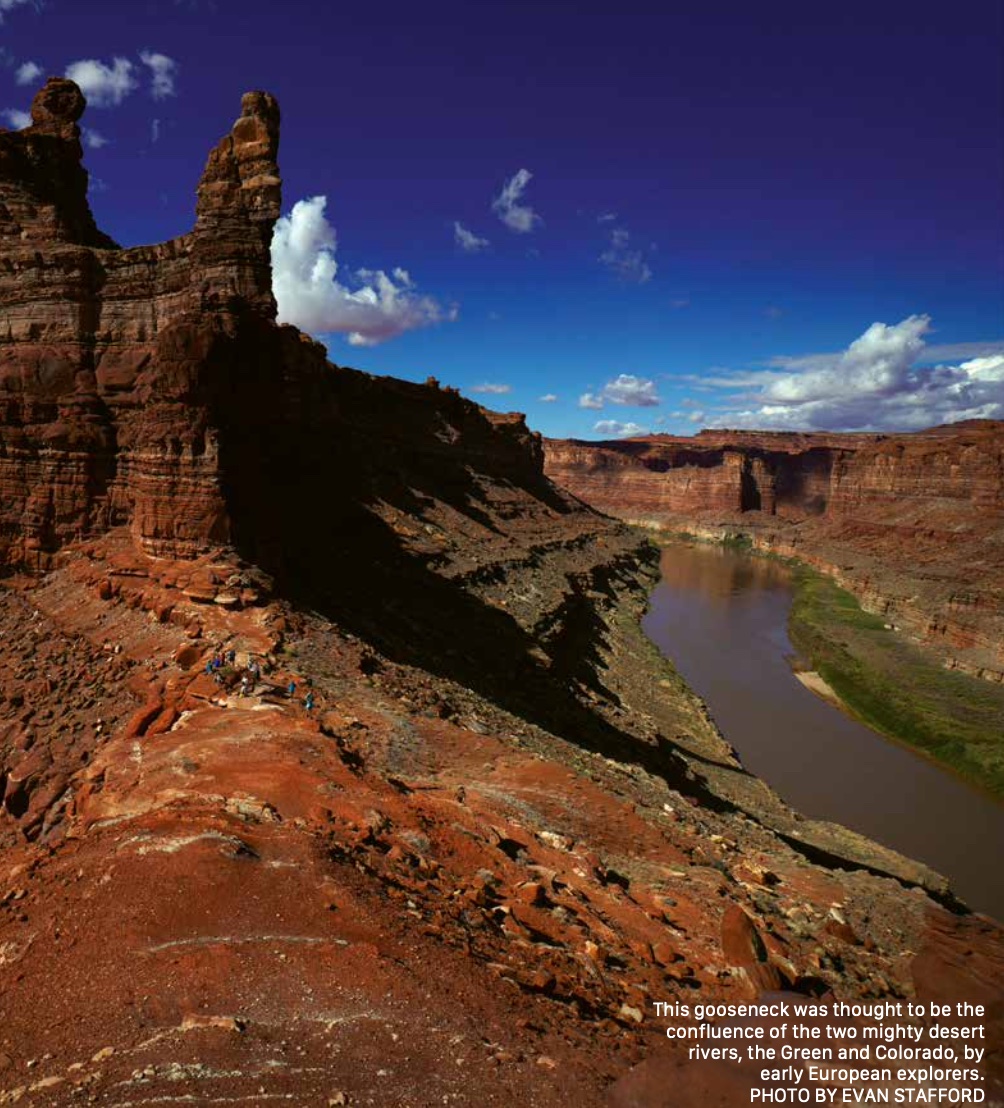

The morning before the confluence, the “hasty team” left early to set up a base RTK GPS unit there so the GCMRC boat could use it as a reference point for their mobile imaging. Meg Flynn led that team, and her group spent all day there at the confluence. The confluence is a powerful place. Two giant western rivers, the Green and the Colorado, meet and mix under a spire of red rock at a huge sandy beach the size of several football fields. That October day, Meg and her team hung out there in a prefrontal windstorm being blasted by sand. But they did their job. They got the RTK base setup so it could talk to the satellites and map this special place.

The Mothership worked its way downstream. We rowed some, went on an adventurous day hike, and collected driftwood to burn. We expected a storm that night. I always try to remain excited about the weather down there, even when I’m camping. Rain in the desert is a beautiful thing. Our flotilla policy conversations tried to answer the question about who was going to manage this “new” river. Glen Canyon National Recreation Area had their hands full moving boat ramps for the reservoir. The Canyonlands National Park boundary ended at the Big Drops. With the changes taking place, we all agreed that a new management strategy must be developed, and soon.

The next morning, we broke up our flotilla to row the whitewater. Mike and Pete helped us find the lines, and by Big Drop 3 the whole crew was feeling good. Mike stood on a dark boulder next to the rapid and carefully explained how to time a pull to thread the needle into the current and run the slot cleanly. Everyone nodded, wide eyed. One by one, we rowed out and shot through the wild constriction, staying far away from a toothy rock garden that could certainly ruin the day.

Scott Christensen, Glen Canyon Institute board member, and I pulled out into the water and slowly rode out onto the tongue. He made a quick motion with his oar in the water and pointed the boat straight into the wild raging river between the rocks. And in a roaring moment of spinning and splashing, the river took us for a ride. I got a face full of Colorado River water and for a minute could only hear its roar. Scott kept it upright, and as quickly as it had started, the rapid was over. We popped out at the bottom to cheers from our teammates.

Now, below the Big Drops, it was time to get to work. That night, at High Stand camp below the rapids, Cari Johnson, a geologist from the University of Utah, explained what we had seen in Waterhole Canyon the year before, and why that place was a great laboratory for understanding sediment transport throughout the Colorado Plateau region. She showed us all a diagram of layers of lake sediment there and how quickly they have changed over the last 70 years. To scientists like her, it is like watching geological processes that usually take millions of years happen in real time. Hearing how quickly the works of man have changed this place left more questions in my mind for what the future would hold.

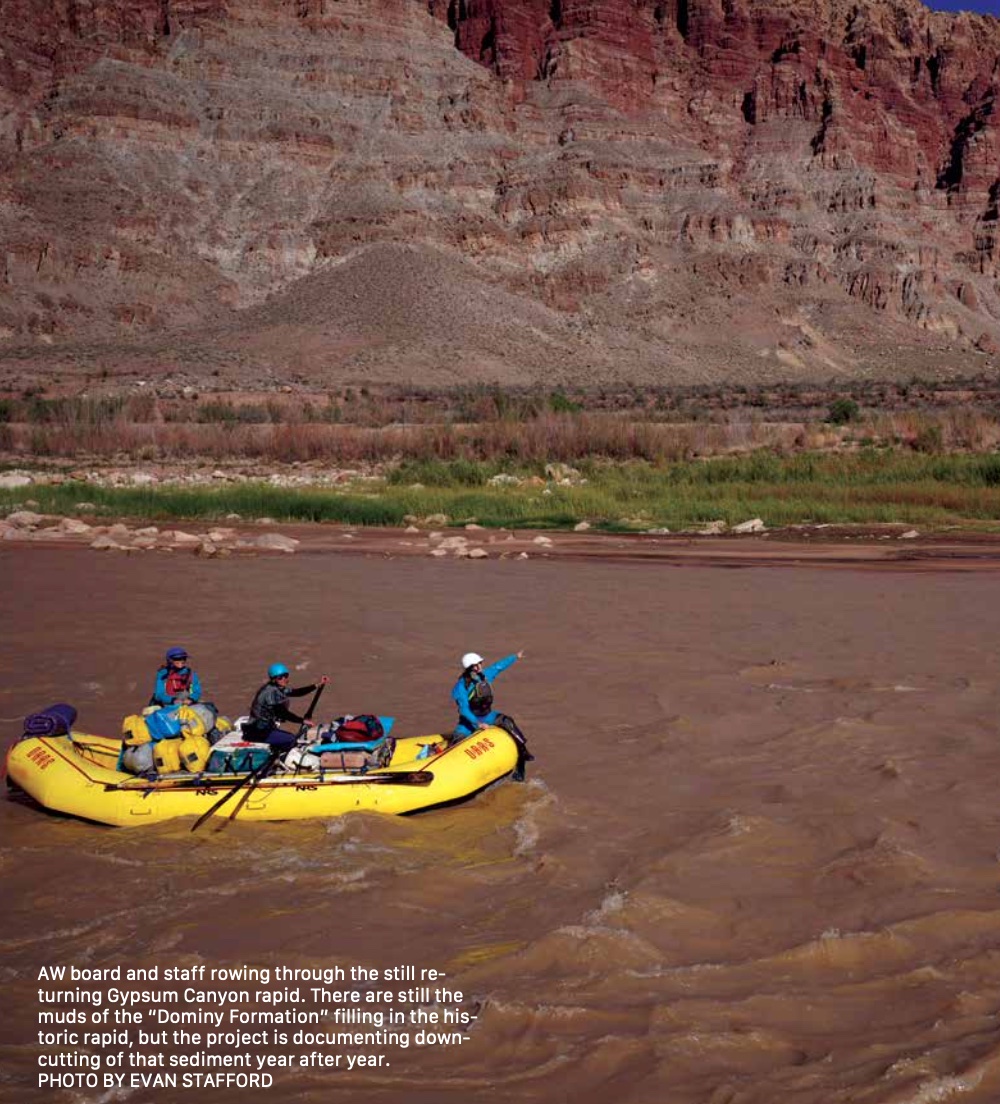

Her presentation was a great prep for the day to come. The USGS, Utah State, and University of Utah researchers would spend all day there. The “hasty team” would cruise down to Gypsum Rapid, where side missions near Imperial Canyon and Gypsum would take place. Dinner and drinks that night were jovial. We were all excited to get to experience the returning rapids that Mike and Pete were so passionate about. I understood why it mattered to track what was happening in this wild place.

In the morning, the geologists settled into a long day, exploring, surveying, and sampling Waterhole. The survey team continued

mapping the river, and the fish people trapped fish. It was awesome to see the team of geologists really digging into Waterhole, as I had spent a fair amount of time the year before getting baseline GPS data. They trundled around in the “Dominy Formation” (sediment banks left by Lake Powell), seeing how the sediment was deposited and how it was eroding.

I spent parts of the next couple of days with Seth Arens from Western Water Assessment, retracing plan surveys in side canyons. The transects he had established from the previous years covered a lot of ground and it was interesting to see what had changed year over year.

The most astonishing thing that had happened over the course of the previous season was the radical monsoon events that took place, specifically in Gypsum, Clearwater, and Dark Canyons. We explored these places during the last two days; they are by far some of the most beautiful and overlooked canyons in the whole area. Until recently the reservoir and sediment made access difficult. Just a couple months of flash flooding in Clearwater and Dark Canyons flushed decades of lake sediment out into the Colorado. Newly exposed bedrock, waterfalls, and alcove features astonished us all as we looked at fossils, and hiked

through returning willows, ash, and cottonwoods. Creeks and streams glistened among fluted red rock slots and waterfalls. It’s truly an amazing place to experience as it returns from inundation.

We motored out the last 20 miles on river current. What was once a river drowned was flowing again. We caught up to a single boat. Jack Schmidt rowed alone through the returning Colorado. His grin grew wide as we caught him. He exclaimed how amazing being on what was once considered gone now felt: at once peaceful, powerful, and worth protecting.

We arrived at the notorious North Wash boat ramp late in the afternoon and made one more camp. RJ, a river guide from Boulder City, Jamie, and I drove a truck up far from the river’s edge to the old shoreline of Lake Powell, half a mile from our camp. We dug through ancient Powell driftwood, collecting pieces to burn. Scorpions darted from our headlamp glow and we smiled, noting that the reservoir would likely never reach there again. Burning that wood, washed down in high flows from the ‘80s with the whole group was cathartic. An elegy for the 20th Century

and its want to control water in the West. The questions came up again. Who would manage this place? How would we rethink our relationship to the water and the land that was coming back to life? Who would manage this massive amount of sediment we had been traveling through? These questions need to be answered and the Returning Rapids project is exposing just how quickly things are changing.

At the end of our trip, we spent hours rolling a dozen boats up to their trailers. After that muddy work was over, we all hugged and said our goodbyes. While I ended with almost more questions than I started with, the science trip and crew that joined it gives me inspiration. It proves that people do care about this place and the future of it. Through collaboration and hard work we can find solutions that protect it for the simple reason that a river must flow. A river will flow.