In Carbon Canyon

In Carbon Canyon

Written by Daryl Ditz, Submitted by Cheryl Ford

I’m perched on a pillow-shaped rock in an unremarkable side canyon, gazing across the Colorado River at the towering cliffs, 4000 feet overhead. It’s a magnificent slice of Grand Canyon’s layer cake of stone, each formation flaunting its colors, textures, and fault lines. All laid bare as the water carves its way through the ages.

The pale Kaibab limestone and khaki-colored Coconino sandstone formed 270 million years ago on an ocean floor, but now they form rocky frosting on top, leaning back to stare into the setting sun. Just below, the Hermit shale spills its crust of dusty rose, leaving splintered towers and angular crannies like the desert forts of Rajasthan, but baked in place 350 million years before the Silk Route. The mahogany dust of Supai and Hermit stains the sheer Redwall limestone beneath, weaving a stunning 500-foot cliff that ribbons through the Canyon for miles.

Further down the slope the remnants gather: limestone, shale, sandstone. It is a kaleidoscope of rocks, grinding its way down. The ancient layers beneath were formed over 600 million years ago. But squint and you can make out shapes; concrete curtains, crumbling grain silos, hoop dresses knit from boulders, stones, and dust. Some rocks calve off like receding glaciers, dropping slabs onto the terraced steps below. Until it all disappears into the black-emerald river, whipped white today by a wicked headwind.

Further down the slope the remnants gather: limestone, shale, sandstone. It is a kaleidoscope of rocks, grinding its way down. The ancient layers beneath were formed over 600 million years ago. But squint and you can make out shapes; concrete curtains, crumbling grain silos, hoop dresses knit from boulders, stones, and dust. Some rocks calve off like receding glaciers, dropping slabs onto the terraced steps below. Until it all disappears into the black-emerald river, whipped white today by a wicked headwind.

I pivot to take in Carbon Canyon, my back to the river, and would assume it is nothing special. Not a particularly beautiful, historical, challenging, or ecologically important site. Easy to ignore, just another dark fold in the overwhelming parade of stone on the Colorado, spilling debris into the river and creating a beach for tired rafters, 65 miles into our journey.

At the mouth of this side canyon, gravel and sand cover our sun-burnt campsite, interspersed with tents, gear, and cacti. Earlier this morning we wandered up this desolate dry wash, a minor hike, maybe a mile and a half, up fairly gradually about a thousand feet, to explore its secrets and peek at the North Rim in the distance.

At the mouth of this side canyon, gravel and sand cover our sun-burnt campsite, interspersed with tents, gear, and cacti. Earlier this morning we wandered up this desolate dry wash, a minor hike, maybe a mile and a half, up fairly gradually about a thousand feet, to explore its secrets and peek at the North Rim in the distance.

As we enter there are few signs of life, suggesting some moisture beneath the surface: bustling red ants, acrobatic lizards, a few flitting birds. Gnarled mesquites, and other die-hard trees, litter the opening. Some held on patiently for centuries, and a few blackened trunks are uprooted, tangled like antlers, long ago forgotten shade.

A thicket of tamarisk adds a splash of green. I keep my distance from this nasty, invasive shrub, recalling past scrapes, welts, and itching on my shins. A bane of rafters and hikers, the plant was introduced to “stabilize” the Canyon’s ever-eroding shore, and it took over beaches all along the river. After decades of axing, poisoning, and burning the tamarisk, it is succumbing to an imported beetle that withers its branches.

A thicket of tamarisk adds a splash of green. I keep my distance from this nasty, invasive shrub, recalling past scrapes, welts, and itching on my shins. A bane of rafters and hikers, the plant was introduced to “stabilize” the Canyon’s ever-eroding shore, and it took over beaches all along the river. After decades of axing, poisoning, and burning the tamarisk, it is succumbing to an imported beetle that withers its branches.

Ahead is a well-defined trail, bracketed by stone walls on either side. Our group started out casually and split up to explore, looking for the easiest way up. But we found ourselves in a jumble of inconvenient large blocks and retreated to the canyon floor. Reunited, we scamper up the chutes and dry pour-overs with little more that water, snacks, hiking stick, and camera. It is an easy stroll up, plenty of handholds. The abrasive texture grips my boots. You will encounter no warnings signs in the backcountry free-for-all. But danger is written on every loose stone, just as it hides in a momentary slip on a slick raft, or twilight call of nature.

As we wander up, everything intrigues. Stone walls are scooped like melting ice cream in a bucket. The shade swings from left to right and back, peculiar stones scatter randomly waiting to be noticed. We follow the path as it snakes up the sinuous curves. Strange marks on the wall suggest graffiti.

As we wander up, everything intrigues. Stone walls are scooped like melting ice cream in a bucket. The shade swings from left to right and back, peculiar stones scatter randomly waiting to be noticed. We follow the path as it snakes up the sinuous curves. Strange marks on the wall suggest graffiti.

We are bake among the rock chutes, boulders, and scoured sidewalls. But the unseen powerful force is water, a reminder that dark clouds beyond our view could trigger a flash flood. Side canyons like Carbon become violent rock spillways during heavy downpours in the brief rainy season. For now, all is stable and safe, baked in suspended animation.

The walls and pour-overs are bone dry, but water sculpted this serpentine course from top to bottom. When seasonal rains rumble over the North Rim, these side-canyons like Carbon can flood and roar, causing rocks as large as kitchen appliances to rattle and shimmy, eventually teetering over a ledge, to chip and crack, the violence of gravity.

The walls and pour-overs are bone dry, but water sculpted this serpentine course from top to bottom. When seasonal rains rumble over the North Rim, these side-canyons like Carbon can flood and roar, causing rocks as large as kitchen appliances to rattle and shimmy, eventually teetering over a ledge, to chip and crack, the violence of gravity.

Today, Carbon Canyon welcomes our fellow rafters and takes kindly to our awe and amazement. Halfway up we encounter a major rock fall, a few stories tall, the result of some fierce collapse, requiring a little ad hoc scampering. Over the years, rangers with steel tools and strong backs have fashioned a safe enough trail for day-trippers like us. We rest in in scarce shade, rehydrate, snack, and stare at the random shapes across the way, as if they hold some secret code.

Refreshed, we rejoin the S-curves upward and the slope begins to flatten as we near the plateau where the canyon makes its initial fold. The shade disappears and enter a scorching desert. We peer into the next canyon over, which leads back to the Colorado down a similar slot, stopping to marvel at the delicate cacti blossoms, pink and magenta. I struggle to grasp the scale of this high desert panorama, and my relation to it … as the North Rim hems the horizon.

Refreshed, we rejoin the S-curves upward and the slope begins to flatten as we near the plateau where the canyon makes its initial fold. The shade disappears and enter a scorching desert. We peer into the next canyon over, which leads back to the Colorado down a similar slot, stopping to marvel at the delicate cacti blossoms, pink and magenta. I struggle to grasp the scale of this high desert panorama, and my relation to it … as the North Rim hems the horizon.

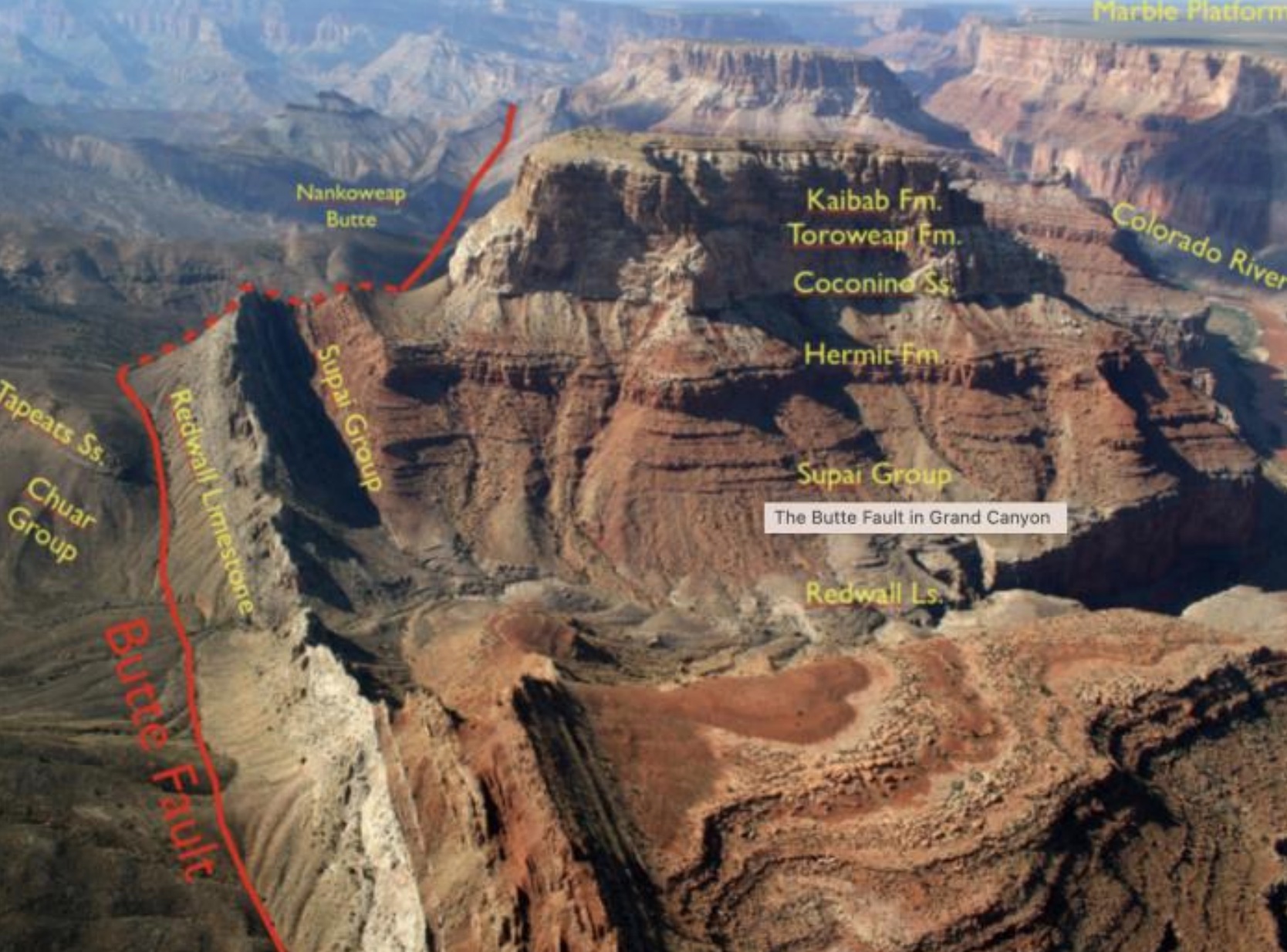

Suddenly, it hits me. A great invisible force has twisted Grand Canyon’s flat symmetry to vertical. Some unimaginable violence flipped the rocky cake on its ear, stone sheets jutting to the sky. Like boards against a slumping barn, or some dusty old geology books that none of us bothered to read.

[Note: After leaving the Canyon I learned that modest Carbon Canyon is considered geologically fascinating, in part due to the massive “butte fault,” that sent the land lurching up a thousand feet. This was the mighty force that upturned the landscape, scrambling new and ancient formations. Live and learn. Thanks to Wayne Ranney, ranger, geologist, educator, and Canyon lover for the insights. Here’s some background about the Butte fault, near Carbon Canyon, thanks to Arizona Geology Magazine.]